My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a Master’s degree in Archives Management at the University of Haute-Alsace, in France. This year, I got the incredible opportunity to spend five months as an intern at the Centre for Research Collections, at the University of Edinburgh. I’ve always been interested in Scotland for its landscapes, culture and history and I was eager to discover more on Scotland through archives. I specifically wished for my internship to be at the University of Edinburgh because of the wide range and diversity of its collection in terms of time period, subjects and materials. I was also curious to see how Archives are considered and handled in the UK and how different, or similar, it is to the way Archives and heritage are seen in France.

During this internship, I have been cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell (1902–1989), a professor of Law at the University of Edinburgh.

Pauline at her desk.

Who was Archibald Hunter Campbell?

Born in Scotland in 1902, Archibald H. Campbell had an interesting academic journey. He was educated at George Watson’s College in 1919, at Edinburgh’s University, before heading to Oxford, where he pursued the Literae Humaniores course (also called ‘Greats’) then completed a Law degree from 1925 to 1927. His intellectual prowess earned him a fellowship at All Souls College in 1928. Later, in 1936, he became Professor of Jurisprudence at the University of Birmingham before taking up a role as Chair of Public Law at Edinburgh University. In 1958 he became Dean of the Faculty of Law. Beyond his academic life, Campbell contributed to history with his involvement during World War II, as he served as a codebreaker at Bletchley Park. There, he was decrypting non-Enigma signals from German, Italian and Japanese Air Forces and producing intelligence reports.

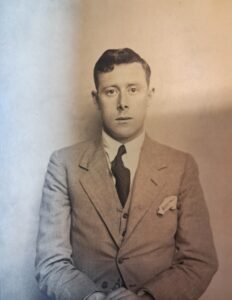

Undated photograph of Archibald H. Campbell.

The papers and their richness

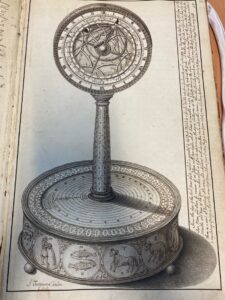

Campbell’s private papers housed at the University of Edinburgh are wonderfully diverse, ranging from papers relating to his personal life (letters, photographs, genealogical documents, postcards collection and diaries) as well as documents relating to his professional life (notes on classes of Roman Law, Civil Law, International Law, Jurisprudence and juristic cases, literature studies booklets and publications on Law and Jurisprudence from himself and his European colleagues). Given the scale of the collection and the limited timeframe of my internship, I focused primarily on cataloguing the correspondence, a very diverse and interesting mission.

A window into History

Spanning from the 1920s to the 1980s, Campbell’s letters offer a peek not only into his personal and professional life but also into significant moments in history: Political movements (Hitler and Mussolini’s whereabouts in the 30s as well as the ascension of fascism), historical events in the UK (like the UK’s general strike of 1926 and UK’s general elections) but also in East Asia (such as the Shanghai International Settlement and the Second Sino-Japanese War), cultural shifts (for instance the progress of medicine and surgery in the 60s, artificial insemination in the UK and its practice in the USA in the late 40s or homosexuality in the eyes of the Law in the 60s), and Edinburgh during the war (shortage in butter, cigarettes, cups and sweets; police activities such as rounding all the Italian ice cream merchants; occasional raids and bombing). His correspondence also reflects rich discussions on music, fine arts, travels across Europe (with a particular fondness for Italy, France, and Germany), and on literature (mostly French and English Literature). These discussions on literature offer a good window into who the famous writers were in France and the UK at the time, and offer interesting views and opinions on the books and their authors.

One of the most striking aspects of his letters is the extraordinary network he maintained. Campbell was in touch with a variety of influential figures: politicians, doctors, artists, historians, writers, philosophers, scholars and barristers. Some of his more commonly well know friends and correspondents include W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Christopher Isherwood. The intellectual exchanges between these individuals are a much interesting glimpse into the literary and academic circles of the time.

My favourite ‘discoveries’

While cataloguing Archibald H. Campbell’s correspondence, I had my personal favourites among his correspondents. Here are the three who stood out the most to me:

John Blomshield, a painter and portraitist who, though relatively unknown today, was well-regarded in his time. His work has been exhibited in leading galleries and museums in the major cities in the USA as well as in Paris, Rome, Oslo, the Far East and South America. He has painted portraits of various authors such as Ernest Hemingway or Scott Fitzgerald. What made his correspondence fun is the drafts of his portraits attached to the letters

Drawings by John Blomshield, dated somewhere between the 30s and the 40s.

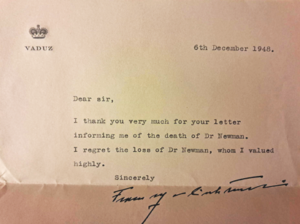

Keith Newman, a pathologist at the County and City of Oxford Mental Hospital. His letters revealed friendships with members of European royal families — including those of Liechtenstein, Great Britain, and Austria. In his letters, Newman refers to the Prince Albrecht Schaumburg-Lippe as “his friend”, and mentions being invited by Prince Omar Halim, cousin of the king of Egypt, to fly to London with him. Keith Odo Newman was a rather influent person in the field of medicine and we know from a cutting from The Daily Mail dated May 1930 included in this correspondence that in he devised a blood-test whereby general paralysis may be detected in its early stages, which was a “remarkable advance” from the previous methods. This discovery represented, at the time, a new hope to find a cure for the disease.

Letter from Franz Joseph II, prince of Liechtenstein, regarding Newman’s passing

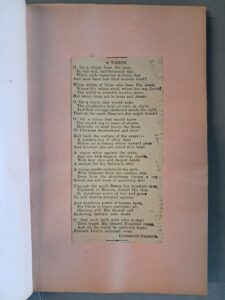

Catherine Gilmour, a friend of Archibald Campbell’s mother (Mary Campbell, fl 1881-1954) whom the correspondence includes a dozen of her poems that were published in newspapers at the time. These poems were very pleasant to read and offered a different format from the letters.

Poems by Catherine Gilmour

Poems by Catherine Gilmour.

I also enjoyed cataloguing the 2 boxes containing the ‘Correspondence of possible juristic interest’. These professional letters focus on discussing and reviewing various publications (books, essays and articles) on Law and Jurisprudence with other European professors and researchers. These letters offered a break while cataloguing the usual personal letters (which can sometimes be monotonous) as they contain a great deal of knowledge regarding Law and Law Studies. Such correspondence could be very useful and enriching for Law students as they gather intellectual thinking and opinions and provide several bibliographical references.

My experience with cataloguing the Campbell’s letters

While cataloguing Campbell’s correspondence, I came across a few difficulties such as reading certain letters with poor handwriting, identifying the authors of the letters and identifying the letters containing personal data and sensitive personal data. Despite these occasional struggles, the cataloguing process was very smooth! I learned a lot on general history and sometimes witnessed very captivating discussions between highly intellectual people on various subjects. The letters offer deep insights into both personal and intellectual history, and it was very enriching to catalogue these papers in a way that will help future researchers.