Home University of Edinburgh Library Essentials

July 22, 2025

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a Master’s degree in Archives Management at the University of Haute-Alsace, in France. This year, I got the incredible opportunity to spend five months as an intern at the Centre for Research Collections, at the University of Edinburgh. I’ve always been interested in Scotland for its landscapes, culture and history and I was eager to discover more on Scotland through archives. I specifically wished for my internship to be at the University of Edinburgh because of the wide range and diversity of its collection in terms of time period, subjects and materials. I was also curious to see how Archives are considered and handled in the UK and how different, or similar, it is to the way Archives and heritage are seen in France.

During this internship, I have been cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell (1902–1989), a professor of Law at the University of Edinburgh.

Pauline at her desk.

Who was Archibald Hunter Campbell?

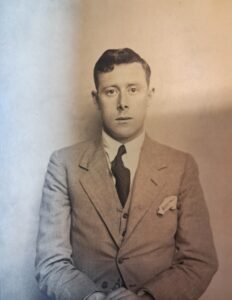

Born in Scotland in 1902, Archibald H. Campbell had an interesting academic journey. He was educated at George Watson’s College in 1919, at Edinburgh’s University, before heading to Oxford, where he pursued the Literae Humaniores course (also called ‘Greats’) then completed a Law degree from 1925 to 1927. His intellectual prowess earned him a fellowship at All Souls College in 1928. Later, in 1936, he became Professor of Jurisprudence at the University of Birmingham before taking up a role as Chair of Public Law at Edinburgh University. In 1958 he became Dean of the Faculty of Law. Beyond his academic life, Campbell contributed to history with his involvement during World War II, as he served as a codebreaker at Bletchley Park. There, he was decrypting non-Enigma signals from German, Italian and Japanese Air Forces and producing intelligence reports.

Undated photograph of Archibald H. Campbell.

The papers and their richness

Campbell’s private papers housed at the University of Edinburgh are wonderfully diverse, ranging from papers relating to his personal life (letters, photographs, genealogical documents, postcards collection and diaries) as well as documents relating to his professional life (notes on classes of Roman Law, Civil Law, International Law, Jurisprudence and juristic cases, literature studies booklets and publications on Law and Jurisprudence from himself and his European colleagues). Given the scale of the collection and the limited timeframe of my internship, I focused primarily on cataloguing the correspondence, a very diverse and interesting mission.

A window into History

Spanning from the 1920s to the 1980s, Campbell’s letters offer a peek not only into his personal and professional life but also into significant moments in history: Political movements (Hitler and Mussolini’s whereabouts in the 30s as well as the ascension of fascism), historical events in the UK (like the UK’s general strike of 1926 and UK’s general elections) but also in East Asia (such as the Shanghai International Settlement and the Second Sino-Japanese War), cultural shifts (for instance the progress of medicine and surgery in the 60s, artificial insemination in the UK and its practice in the USA in the late 40s or homosexuality in the eyes of the Law in the 60s), and Edinburgh during the war (shortage in butter, cigarettes, cups and sweets; police activities such as rounding all the Italian ice cream merchants; occasional raids and bombing). His correspondence also reflects rich discussions on music, fine arts, travels across Europe (with a particular fondness for Italy, France, and Germany), and on literature (mostly French and English Literature). These discussions on literature offer a good window into who the famous writers were in France and the UK at the time, and offer interesting views and opinions on the books and their authors.

One of the most striking aspects of his letters is the extraordinary network he maintained. Campbell was in touch with a variety of influential figures: politicians, doctors, artists, historians, writers, philosophers, scholars and barristers. Some of his more commonly well know friends and correspondents include W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Christopher Isherwood. The intellectual exchanges between these individuals are a much interesting glimpse into the literary and academic circles of the time.

My favourite ‘discoveries’

While cataloguing Archibald H. Campbell’s correspondence, I had my personal favourites among his correspondents. Here are the three who stood out the most to me:

John Blomshield, a painter and portraitist who, though relatively unknown today, was well-regarded in his time. His work has been exhibited in leading galleries and museums in the major cities in the USA as well as in Paris, Rome, Oslo, the Far East and South America. He has painted portraits of various authors such as Ernest Hemingway or Scott Fitzgerald. What made his correspondence fun is the drafts of his portraits attached to the letters

Drawings by John Blomshield, dated somewhere between the 30s and the 40s.

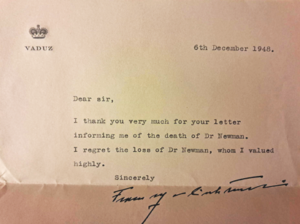

Keith Newman, a pathologist at the County and City of Oxford Mental Hospital. His letters revealed friendships with members of European royal families — including those of Liechtenstein, Great Britain, and Austria. In his letters, Newman refers to the Prince Albrecht Schaumburg-Lippe as “his friend”, and mentions being invited by Prince Omar Halim, cousin of the king of Egypt, to fly to London with him. Keith Odo Newman was a rather influent person in the field of medicine and we know from a cutting from The Daily Mail dated May 1930 included in this correspondence that in he devised a blood-test whereby general paralysis may be detected in its early stages, which was a “remarkable advance” from the previous methods. This discovery represented, at the time, a new hope to find a cure for the disease.

Letter from Franz Joseph II, prince of Liechtenstein, regarding Newman’s passing

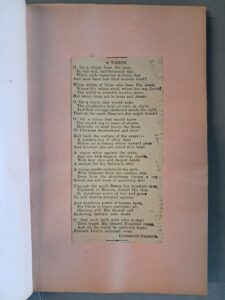

Catherine Gilmour, a friend of Archibald Campbell’s mother (Mary Campbell, fl 1881-1954) whom the correspondence includes a dozen of her poems that were published in newspapers at the time. These poems were very pleasant to read and offered a different format from the letters.

Poems by Catherine Gilmour

Poems by Catherine Gilmour.

I also enjoyed cataloguing the 2 boxes containing the ‘Correspondence of possible juristic interest’. These professional letters focus on discussing and reviewing various publications (books, essays and articles) on Law and Jurisprudence with other European professors and researchers. These letters offered a break while cataloguing the usual personal letters (which can sometimes be monotonous) as they contain a great deal of knowledge regarding Law and Law Studies. Such correspondence could be very useful and enriching for Law students as they gather intellectual thinking and opinions and provide several bibliographical references.

My experience with cataloguing the Campbell’s letters

While cataloguing Campbell’s correspondence, I came across a few difficulties such as reading certain letters with poor handwriting, identifying the authors of the letters and identifying the letters containing personal data and sensitive personal data. Despite these occasional struggles, the cataloguing process was very smooth! I learned a lot on general history and sometimes witnessed very captivating discussions between highly intellectual people on various subjects. The letters offer deep insights into both personal and intellectual history, and it was very enriching to catalogue these papers in a way that will help future researchers.

Summer hours at Old College

Chrysi Chrysochou, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

You’d be forgiven for thinking that the warm weather recently means we’re already in the middle of summer, but as the semester is only just reaching its conclusion we do need to alert you to some changes coming up in Old College as of Monday 26th May.

The Law School is moving to Summer Hours which means that the building will close at 6pm each day from now until September. Unfortunately this means the Quad Cafe will also be closed for the summer, so you may have to travel further afield for your caffeinated study breaks!

The Law Library will now be open 9am to 5pm Monday to Friday and closed on Saturdays and Sundays. Please note that the Helpdesk will close at 4.50pm each day to allow our staff sufficient time to enact our closing procedures.

The Main Library will still have study space available at the weekends throughout the summer, check the Library Opening Hours website for more information.

Library staff will be available throughout the summer to answer any queries you have so if you need to get in touch please drop us an email.

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation

My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student. As I enter my final year of undergraduate history, I have come to appreciate the importance of physical archives for historical research, especially for history beyond ideals and representations. My research interests lie in 20th century global history, with a particular focus on gender, sexuality and East Asian ethnic subjectivities. Finding archival material for my research is, by the nature of my interests, thematically and geographically difficult. I later realised that they are held in institutions all over the world, in Europe, America and Asia, with only a small proportion digitised and available for my research. This inspired me to learn more about archives and digitisation, and perhaps to contribute to the process. With a desire to touch some physical manuscripts, this Archival Provenance Research Assistant internship appealed to me.

Lishan at her desk.

Paleography

At first, I was quite nervous about my never-learned palaeography skills, apart from a talent for chaotic writing, as this position requires reading and transcribing handwriting, mostly from the early 20th century and occasionally from the 16th to 19th centuries. As a non-native speaker of English, my biggest challenge is the name of places and people. While I can make sense of the rest with contextual interpretation, many English and Scottish names (especially as they have variations in older forms) are completely foreign to me. Fortunately, my line manager Aline has been very warm and supportive, seeing through my nervousness and encouraging me to practice bit by bit. I have learnt to look up to confirm the spelling of names and to become more familiar with certain words related to the archival catalogue.

Provenance information creation

One of the main tasks of this internship is to comprehend the provenance information for two of the University’s legacy sequences, “Dc” and “Dk”, based on the information contained in an early twentieth-century registers, and to do further confirmation with the physical manuscripts. Provenance refers to the original source of an item and its history of transactions, which is important for historians to understand why an item was created and in what context. The collections typically contain items such as letters from intellectuals and aristocrats, lecture notes on medicine, law and philosophy, newspaper cuttings and manuscripts of books. Most of the people involved were either Scottish or concerned with Scotland in some way. Several times, as I tracked down the information of the related individuals, I found out that they lived on the very streets I passed in Edinburgh. I feel like a detective in locating the identities of these people. For example, I was checking the identity of an author of several letters who called himself “John Brown,” and later it turned out that there were four “John Brown” co-authors of these letters! Because Dr John Brown (1810-1882), shared the same name with his cousin, John Brown of Burnley (1842-1929), his son John Brown of Balquancal, and his father, Professor John Brown (1784-1858). It’s fascinating to see interactions between well-known figures back and forth on paper, revealing unexpected connections in the past. However, this documentation of certain subjects and the correspondence of certain individuals in the archives also highlight the socially constructive nature of historical preservation. That is, it is usually the more privileged social class, gender and ethnic group who were able to create and preserve their prints in visible forms.

Physical items

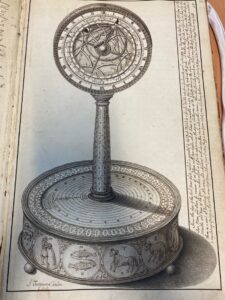

Perhaps the most enjoyable part of this internship is being able to touch the physical manuscripts. I have learned about their temporality through their fragility and the “encoding” of words that time has naturally created: labour for historians, beyond the more visible work of interpretation and presentation. It is also beautiful to have a visual representation of the intellectual labour of the past, and how it differs from that of the present. The following photographs, for example, are of a commonplace book by the Scottish astronomer James Ferguson, a form of noting and recording knowledge that was common in the eighteenth century.

Coll-2222, Volume entitled “James Ferguson’s Common Place Book”, c 1775 (Dk.7.33)

Coll-2222, Volume entitled “James Ferguson’s Common Place Book”, c 1775 (Dk.7.33)

Wider work and learning

The workplace is the University of Edinburgh’s Heritage Collections Office on the fifth floor of the Main Library, overlooking the beautiful Meadows. As a trainee, I am warmly welcomed by archivist colleagues. I am also offered the opportunity to attend a variety of training sessions and events. These include introductions to the storage and conditions of different types of archives, handling manuscripts, and visits to study centres with other archival resources. For my future studies I feel more familiar with finding and contacting the archives, which will be important for historical research at postgraduate level.

Card indexes at the School of Scottish Studies Archives.

View from the office.

An Afternoon with Esther Inglis: Event Summary

This post was written by Jaycee Streeter, Outreach and Communications Intern for the Esther Inglis Project. Jaycee is a History MSc student at the University, with research interests in early modern Scottish literary and religious history.

Event poster for An Afternoon with Esther Inglis (c. 1570-1624)

On Saturday, April 26th, St. Cecilia’s Hall in Edinburgh hosted “An Afternoon with Esther Inglis (c. 1570-1624)”, marking the end of the Esther Inglis 2024 Project, coordinated by Anna-Nadine Pike and Jaycee Streeter. The project has been running at Edinburgh University Library for the last eighteen months, marking 400 years since Esther Inglis death through new research, an online exhibition titled “Rewriting the Script”, and a program designed to bring Esther Inglis story to wider audiences in Edinburgh and beyond. That program included concerts, an international colloquium, a physical exhibition in the Centre for Research Collections, and now, a grand finale with this final public event.

The event aimed to bring Inglis, with her work and context, to the public through a variety of forms—a panel discussion, poetry performance, and musical performance—and a mix of media both contemporary to Inglis and modern but inspired by her.

The panel featured two Esther Inglis experts, Anna-Nadine Pike and Jamie Reid-Baxter, as well as two acclaimed authors who have featured Inglis in their works, Sara Sheridan and Gerda Stevenson. Their discussion was extensive and varied, touching on Inglis’ context in Edinburgh, how we can better tell the stories of Scottish women in this period, their research processes and how they manage/utilize silence in the archives, and the role we can play in commemorating women today. The audience was able to ask questions of the panel, and were curious to know more about Esther Inglis and her story.

Esther Inglis, Octonaries upon the vanitie and inconstancie of the world, 1607. Washington, DC: Folger Shakespeare Library, V.a.92

Then, Gerda Stevenson and Jamie Reid-Baxter brought poetry to life with readings from Inglis’ manuscripts, words written by Inglis herself, and contemporary poetry written praising Inglis and her skills. Reciting in French, English, and Scots, their performance brought the audience closer to Inglis’ life and work.

This was followed by a modern composition, Gerda Stevenson’s own “Nine Haiku for Esther Inglis” which is featured in her poetry collection, “QUINES: Poems in tribute to women of Scotland.” She discussed her inspiration for the poem and the emotional connection she felt with Inglis, and the other women featured in the collection.

Then, the White Rose Ensemble took the stage. The Ensemble, founded in 2017 by soprano Sally Carr and clarinetist Calum Robertson, is an Edinburgh-based duo known for their innovative chamber music rooted in Scottish and contemporary traditions. They were joined by pianist Ailsa Aitkenhead. Together, they played psalms featured in Inglis’ manuscripts and two songs written by contemporary Scottish women, showing the audience the music that Inglis would have engaged with in her lifetime.

The White Rose Ensemble

The event concluded with a modern composition by Sheena Phillips, set to the text of Gerda Stevenson’s “Nine Haiku for Esther Inglis,” which Phillips describes as, “marvellous vignettes of key aspects of Esther’s life and work, and full of musical possibilities. The musical setting of the haiku deliberately echoes aspects of Esther’s work.”

This blending of Inglis’ work and work contemporary to her and modern art inspired by it embodies the goal of this event, and in a greater sense, the whole Esther Inglis Project. If the panel posed the question, “How can we commemorate women like Esther Inglis today,” then the rest of the program gave a resounding answer: Celebrate them, remember them and speak about them, and continue to let their stories inspire future generations through art and memory.

Sally Carr, Calum Robertson, Anna-Nadine Pike, Ailsa Aitkenhead, Gerda Stevenson, and Jamie Reid Baxter

…

On a personal note, being the Outreach and Communications Intern for this Project has been not only an honor, but a joy. Through the events hosted this spring, I got to know a community passionate about learning and celebrating early modern Scottish women. I learned valuable lessons about engaging with the public in matters of history (and broadened by perspective on what “the public” even means), and to not underestimate the amount of interest that exists in even niche historical people and events. I am immensely grateful for my time with the project.

Anna-Nadine Pike, Project Curator, and Jaycee Streeter, Outreach and Communications Intern

VE Day: through our online resources

Today, 8 May 2025, marks the 80th anniversary of VE Day (Victory in Europe Day) when people in Britain and Allied nations across the world celebrated the unconditional surrender of Germany in the Second World War. While it was not the end of the conflict (it was August 1945 before the war against Japan ended) the sense of relief for people who had been living under total war for 6 years was huge. In Britain VE Day was declared a national holiday and people took to the streets to celebrate and commemorate in a huge release of collective tension. This blog posts pulls together just a small selection of our digital library resources that will help you find out more about VE Day, the events leading up to it and the aftermath.

What did the papers say?

Mentions of VE Day or Victory in Europe Day start before the 8th May, as people were aware of and anticipating the likely German surrender. So some preparations were already underway and some people began to celebrate early, on the 7th, when in Britain it was announced on the radio that the war in Europe was over.

From “This was VE-Day in London.” issue of Picture Post, May 19, 1945. Picture Post Historical Archive, 1938-1957.

“Happy Notebooking”; reflections on the Lyell Access and Engagement Programme (LAEP)

Over the past five years, the University of Edinburgh has undertaken a transformative programme to catalogue, preserve, and enhance access to the Charles Lyell Collection. This final blog marks a key milestone—sharing outcomes, showcasing the new catalogue and website, and offering tips for using this vast resource, while also pointing ahead to future discoveries.

Lyell in 1842 as featured in ‘Lyell in America : transatlantic geology, 1841-1853’ by Leonard G. Wilson, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. Our research has not been able to confirm the whereabouts of the original image.

In The Antiquity of Man, Lyell investigated the meaning of prehistoric flint implements, using them to authenticate ground-breaking arguments about humanity’s deep past. We’ve used our own set of tools – archival methods, state-of-the-art digitisation equipment and digital infrastructure – to unlock the full scope of Lyell’s legacy.

AI has offered some useful and interesting tools. Transkribus provided a scaffold for students learning to decipher Lyell’s handwriting, while ChatGPT has at times supported the non-scientist Archivists. In fact, the title of this blog, ‘Happy Notebooking,’ originated from an AI-generated parting, during an early discussion about the Lyell collection. Just as flint tools helped Lyell uncover ancient stories, our digital tools have helped us illuminate his world—transforming his notebooks, correspondence, and discoveries into something accessible for future generations.

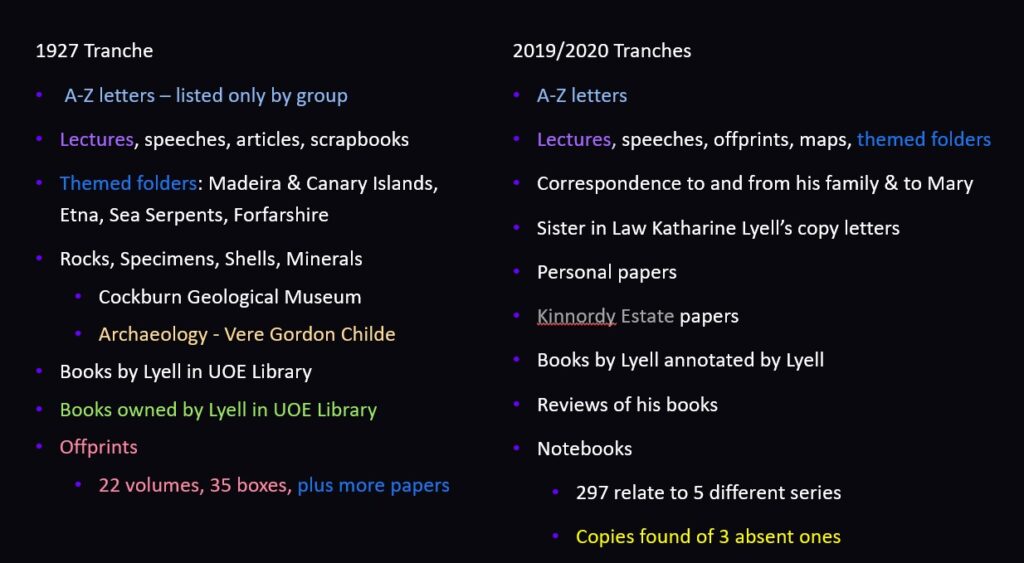

A basic overview, by provenance, of the composition of the Lyell archive collection.

Charles Lyell is never referred to as an Archivist, but his collection serves as both evidence and documentation of the history of the Earth, and, of his role as its information manager. He’s assisted in this work by his team – George Hall, wife Mary Lyell, and Arabella Buckley, maybe even other people we’ve not identified yet. For our project, the decision was taken to respect the provenance of the different accessions of Lyell material held at the University, but, the history of information management is writ large across the collection, and we’ve also used the original organisation created by Lyell and his team, to arrange series.

Our work to develop a comprehensive online catalogue has:

- Expanded the list of correspondents from broad alphabetical categories to over 400 named individuals, providing a clearer picture of Lyell’s extensive network

- Worked to catalogue the Scientific notebooks. This work will be ongoing, with skilled volunteers meticulously adding details for each one

- Mapped the records related to Lyell’s Lectures, uncovering how these early materials, which also illustrate the development of his science communication skills, criss-crossed the Atlantic

- Revealed Lyell’s practice of recording his reading and thoughts in the Index notebooks, and, confirmed the connections with the recently rediscovered Offprints held at the University, and which had previously been challenging to interpret

- Highlighted Lyell’s writing process, through the annotated copies of his books, original manuscript notes, edits, and the publishing activities recorded in the notebooks

- Strengthened the understanding of the connections between Lyell’s geological specimens – rocks, minerals, and shells – and the archive, establishing a clearer provenance for many, with evidence of Lyell’s direct involvement in their acquisition.

Reflecting back, we can confirm we’ve thoroughly enjoyed the challenge of deciphering Lyell’s handwriting! Along the way, we’ve encountered the complexities of outdated scientific terminology, historical – and indeed multiple place names across Europe, the UK, and America – as well as Lyell’s spelling. Lyell is actively listening to what other people are saying, which sometimes leads to misspelling. Please forgive any of our own mistakes you might come across; and don’t hesitate to contact us if we can make corrections.

A big thank you to all the volunteers, who have worked with us over the last 5 years, but especially to Drew Coleman and Beverly Gordon – who have worked diligently since 2023 to add detail to the notebooks, allowing us to work to fulfill our aim of a consistent, rich, level of detail for all 297. We’re particularly proud to have added several women – Mary Anning and Jeanne Villepreux-Power amongst them – to our catalogue, helping highlight their contributions to Lyell’s work.

The Lyell Website: A Digital Gateway to His Legacy

All of this work has contributed to a new website designed to make Lyell’s legacy more accessible to the global audience it truly deserves. The website is organised around Lyell’s principal tools; his archival papers – an inclusive term reflecting the breadth of the material held within – as well as the notebooks, Offprints, and specimens.

Lyell’s books can be a useful starting point for any research, as the archive ultimately informs his published works. In addition to providing links to Lyell’s books published by John Murray online, we are proud to make available the late Stuart Baldwin’s comprehensive bibliography. Do make sure to access this, as it provides an excellent start to understanding the extent of Lyell’s output. Other key sources are Life Letters and Journals of Sir Charles Lyell by Katharine Lyell – also available via on the website – and the works of Leonard G. Wilson.

Of particular note on the website are the images of Lyell’s treasured 297 notebooks, which document his observations from 1818, on a European tour with his family, through to November 1874, just three months before his death. You can access IIIF-compliant images of these notebooks via the “Search the Notebooks” button.

The website offers users an easy way to navigate through the vast collection of materials, creating an interactive experience that aims to preserve and expand upon the legacy of one of the most influential Geologists in history.

Our work has revealed the depths of Lyell’s archive, but there’s more still to be explored. Some series of correspondence and a selection of specimens held at the Cockburn Museum have been photographed, providing exciting opportunities for further research. The voluminous Offprints have been box listed only, but its a start. The research potential is immense – many of the geological features Lyell studied are now important heritage and tourism sites. If you live near one, it’s likely that Lyell visited (and possibly documented it more than once!). His advocacy for using physical collections and his involvement in nineteenth century museum development also merit further study.

Felicity at the official opening of the project exhibition, taken by photographer Neil Hanna 07702246823

Finally, we can introduce you to Felicity Mackenzie, the University of Edinburgh’s newest Lyell enthusiast. Felicity’s PhD will explore Lyell’s legacy, and we’re excited to pass the baton to someone so passionate. Her research promises to utilise the archive to reassess and deepen our understanding of Lyell’s lasting impact. In fact, Felicity is continuing with her own Through Lyell’s Eyes blog – please do subscribe to keep on this epic journey!

US Government Data: Lost and Found

Actions by the current US Trump administration (and others, including Trump’s first term) have spurred archivists, librarians and activists to archive, capture, collect, crawl, hoard, mirror, preserve, rescue, track and save datasets produced at taxpayer expense and until recently made available on government websites.

Actions by the current US Trump administration (and others, including Trump’s first term) have spurred archivists, librarians and activists to archive, capture, collect, crawl, hoard, mirror, preserve, rescue, track and save datasets produced at taxpayer expense and until recently made available on government websites.

For example, just as US federal research into climate change, or even mentioning climate, has been paused and government agencies defunded, so the datasets produced from these activities have been removed from public reach or disappeared. The same is true for health data around vaccine research (National Institutes of Health, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention), human subject data deemed to be furthering EDI – equality, diversity, and inclusion – (USAID), and longitudinal educational data measuring attainment and social mobility (Department of Education). In some cases, as on this US government web page from the National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), there are both items that are being decommissioned and archived, and others that are simply being decommissioned and deleted.

Particular challenges to archiving such data are capturing whole databases from scraping techniques, metadata loss, loss of provenance tracking (audit trail of changes), and the inability to add records or collect further data without massive government investment. Also, isolated efforts mean the data cannot easily be discovered.

Fortunately, the Data Rescue Project is coming to the rescue (along with other initiatives). It is a coordinated effort among data organisations and individuals, including librarians and data professionals. It serves as “a clearinghouse for data rescue-related efforts and data access points for public US governmental data that are currently at risk.” The web page provides a host of pointers to current efforts, resources, a tracker tool, and press coverage – including the New Yorker and Le Monde.

Researchers at University of Edinburgh who find that data they require for their research is being removed from publicly available sites may contact the Research Data Support team to discuss potential actions to take.

Robin Rice

Data Librarian and Head of Research Data Support

Library and University Collections

Papers of Benjamin Leigh Smith: Journal of the Schooner Samson 1871

Today we are publishing an article by Ash Mowat, a volunteer in the Civic Engagement team, on Benjamin Leigh Smith’s voyage to the Artic in 1871.

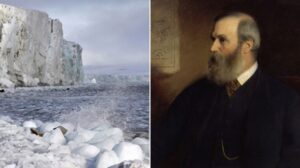

In this blog we shall join the exploration of the voyage by Benjamin Leigh Smith to Svalbard in the Artic in 1871, held at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Research Collections.

Biography of Benjamin Leigh Smith

Benjamin Leigh Smith (1828 to 1913) was an English yachtsman and explorer, becoming famed for his ventures to the Artic. [1] This blog will focus on his 1871 voyage to survey the area of Svalbard, a Norwegian archipelago situated in the Artic Ocean.

(Image of Svalbard and portrait of Benjamin Leigh Smith courtesy footnote 2)

Unlike contemporaries such as Ernest Shackleton, Smith has sadly become less well known for his ambitious and high-risk explorations.[2] He was an early pioneer of travelling to view and survey the Artic region, a very hazardous pursuit given the severe weather conditions and sea ice, and given the frailties and limitations of wooden (albeit reinforced with steel) sailing ships as means of transport.

In a later mission of 1881 aboard the Eira, the vessel was crushed and Leigh Smith and his crew were trapped in ice on land for ten months, having to live in crudely fashioned structures off the ship and hunting local animals for food. Astonishingly all the crew survived, despite having to endure a long return home on small boats with sails fabricated from makeshift materials. A modest man, he never sought the fame and publicity that others in his field sometimes utilised. He was, however, recognised with the award of the Patron Gold Medal, amongst the most esteemed honours granted by the Royal Geographical Society. His family background was interesting and progressive for the time, with his parents not being married which was hugely unconventional for the period. His sister was the celebrated feminist, women’s rights activist and artist Barbara Bodichon,[3] and his cousin was Florence Nightingale.

I viewed Leigh Smith’s handwritten journal on his 1871 mission sailing from Grimsby to Svalbard at the University of Edinburgh’s Centre for Research Collections.[4] In an opening introduction it is recounted that:

“Tropical Schooner Samson, 85 tons register built by Messrs John White, Cowes of Isle of White, was purchased by BL Smith esquire…has made two voyages to Artic regions whilst owned by Mr Pallister. BL Smith esq belongs to the Thames Yacht Club, on a voyage from England to Norway and thence to the Artic regions on a cruise.”

Wednesday 17th May 1871 Leigh Smith records: “Crew employed stowing stores and making ship ready for sea. The crew are all Norwegian and only the captain and mate speak any English”. Later noting “departed Friday 19th May in fair weather with other vessels.”

Recounting some of the restrictions of progress on a heavy ship powered solely by sails he remarks on Monday 22nd May “distance from noon to noon today only 51 miles, a very poor day’s work.” Several days later he reports “passing coast of Norway and much finer calmer weather than anticipated, made progress of 137 miles noon to noon.”

In the following entry Leigh Smith reveals some contrary concerns about the fine weather and some intriguing details of his crew: “Weather remarkably calm and the stillness seems quite oppressive. We have on board in the person of one of the crew, Hans by name, a Norsk Fin…he seems to have some special grudge against the cook, a very inoffensive character, and seizes every opportunity to persecute him more.”

Later Leigh Smith describes a hazardous encounter with a large fish passing when he was aboard a small dinghy. “Fortunately for us, it did not touch the boat or our Artic voyage would have ended in a very brief manner, as there were no boats that could be sent from the ship without some considerable delay getting them off deck”. Somewhat suggestive of some undue risks being taken in this episode that could have proved very costly to lives and the expedition.

On 29th May there is an interesting comparison comment when encountering what would have been an early version of a steamer ship. “We saw a steamer ship during the morning, during the morning, steaming up from leeward who since the wind has freshened has been compelled to resort to tacking, in which method we contrived to beat her. So concluded, as we know we are not a Clipper, that she is a very bad specimen of steam power.” With later advancements if steam technology, such vessels would later become much safer and more efficient means to venture into such hostile seas.

On 3rd June there is a record of a period on land and observations of residents. “Anchored and went ashore at Tromso (Northern Norway). The houses are all built of wood, being varnished in the rooms giving them a light and cheerful appearance. The people dress well and look to be enjoying good health…people do not seem to care about going to bed here. I think they are acting in the old maxim make hay while the sun shines, as they have a long dreary winter, they intend to make up for lost time.” They spent several weeks at Tromso and recruited “an additional crew of five men as foremast men and one harpooner, making 14 in number all told and two dogs”

The following reports contains some descriptions of hunting that may appear jarring and unpalatable to current times but are representative of practices of the period. “We sighted bear island…this afternoon being very calm and clear weather, went out in the dinghy and landed the dogs on the iceberg; they seemed to enjoy the fun immensely… plenty of shooting auks or puffins which are numerous”. “Saw several whales round the ship, got harpoon on the bow loaded with a shell, one came close, an excellent opportunity but unfortunately the shell exploded before reaching the fish.”

Whaling, of course, was a globally widely practiced industry at the time and for many years afterwards, the whales utilised not only as a food source but also the use of whale oil in streetlighting and manufacturing such as in the jute trade.

On 26th August at Spitzbergen, Svalbard he understatedly describes a close encounter: “An immense iceberg came alongside of the ship, towering over the ship like a precipice. We supposed the iceberg not less than 50 feet above the water. We speedily unmoored and got out of the way of such an unwelcome visitor”.

On 2nd September still at Spitzbergen he records a meeting with other vessels: “Two of the other yachts came in for shelter…one of them on the passage from Nova Zemla (Novaya Zemlya) to Spitzbergen met a herd of seals on the fast ice and were fortunate enough to get 200 of them, what with 14 walrus they had previous and five polar bears made them a good catch compared to other vessels.”

Benjamin Leigh Smith, second from left, aboard later expedition on the Eira. Photography courtesy of footnote 2).

It was intriguing to read these notes which give an insight into the extremely challenging and hazardous endeavours to explore such hostile seas in such primitive and vulnerable vessels. The hardiness required and hardships experienced to undertake such journeys must have been considerable.

I should like to thank my supervisor Laura Beattie (Community Engagement Officer) for support and guidance, and to all staff at the Centre for Research Collections for enabling access to view these materials.

[1] Benjamin Leigh Smith – Wikipedia

[2] Benjamin Leigh Smith: The forgotten explorer of the frozen north – BBC News

[3] Barbara Bodichon – Wikipedia

[4] Collection: Papers of Benjamin Leigh Smith | University of Edinburgh Archive and Manuscript Collections

Free University Card Replacement

So, what do you do when your university card is lost, damaged or stolen?

Well, usually you will visit our EdHelp Service Desk in the Main Library or any Card Help Desks and get a replacement card. But, you will need to pay the £10 fee; and the fee applies to all card holders (staff, students and visitors)

But for the next few weeks, between April 21 – May 23 you can get your university card replaced for free!!!

This is a one time, single offer for the duration specified above, so if your card is lost, damaged or stolen, head to one of our card help desks and the super friendly library staff there will be able to help you.

Best wishes

Your Academic Law Librarians

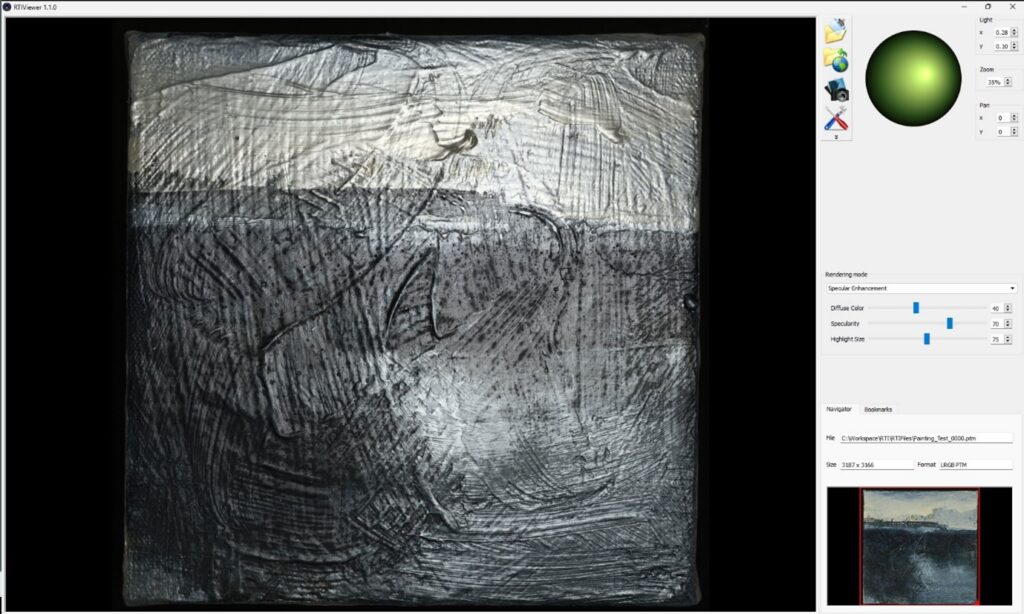

Reflectance (Transformation Imaging) Reflections

Reflectance Transformation Imaging, or RTI as it is more commonly known, is described as ‘a computational photographic method that captures a subject’s surface shape and color and enables the interactive re-lighting of the subject from any direction. RTI also permits the mathematical enhancement of the subject’s surface shape and color attributes. The enhancement functions of RTI reveal surface information that is not disclosed under direct empirical examination of the physical object’ by Cultural Heritage Imaging https://culturalheritageimaging.org/Technologies/RTI/

I think of it as raking light on steroids- essentially you have a camera at the top which fires in sequence with individual lights located in a circle around the item, and then the registered images can be engaged with interactively through the freely available RTI Viewer https://culturalheritageimaging.org/What_We_Offer/Downloads/View/index.html

Collections

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Hill and Adamson Collection: an insight into Edinburgh’s past

My name is Phoebe Kirkland, I am an MSc East Asian Studies student, and for...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Projects

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Cataloguing the private papers of Archibald Hunter Campbell: A Journey Through Correspondence

My name is Pauline Vincent, I am a student in my last year of a...

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....

Archival Provenance Research Project: Lishan’s Experience

Presentation My name is Lishan Zou, I am a fourth year History and Politics student....